Why Music? Memory and Emotion

Dear Reader

This blog is the final part of a 4-part presentation of my script for the Music and Memory lecture, which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on September 27th.

If you wish to catch up, you can read Part 1 of Music and Memory lecture here, Part 2 here and Part 3 here. Part 4 fininshes with a look at the role of emotion in making memories…

——————————————————————————

All three elements of music in memory we have discussed by now – melody, harmony and meaning – arise from music principles that we learn as we are exposed to the music of our own cultures.

When we first listen to the music of a different culture by comparison we can feel lost. Our instinct is to try to force our tried and tested music schemas onto this new sound; when this fails we experience confusion.

The good news is that this state is temporary. The brain has a life-long ability to grow, change and adapt: a trait known as neuroplasticity. We can learn and understand different musical elements and meanings at any age. All that we have to do… is listen. Listen again, and again. As we listen our minds learn the shapes in the melodies, the rules of the variations, and the patterns in meaning. Never be afraid to persist with new music. Your musical memories are willing and ready to be made!

To close our music and memory concert today we explore perhaps the most iconic of music’s general properties that make it a powerful mind stimulant – a unique form of meaning for all of us, whatever our culture: the indelible link between music and emotion.

Despite the variety in the world’s music, and the challenges this presents to the ever-curious listener, there is a clear candidate for a human music universal – the expression of emotion.

In around 380 BC Plato suggested that music has a direct effect on the soul. Both he and Socrates are credited with the theory that music holds power over our minds because of the way it imitates the inflections of the voice that betray human character and emotion.

Other expressions of human emotion, such as facial expressions for sadness and happiness, have long been thought to be universal. Could our expression in music be similarly cross-cultural?

Good evidence for a basic universal emotion in musical understanding emerged in 2009 when Dr Thomas Fritz of the Max-Planck-Institute visited the Mafa tribe in Western Cameroon. The people of this tribe have never been exposed to Western tonal music. Would they recognise the expressions of emotion therein?

Dr Fritz played the Mafa instrumental Classical, Jazz (Herb Alpert) and rock’n’roll music, and asked them to identify the emotion by pointing to cards with pictures of happy, sad, or fearful faces.

The Mafa were not as accurate as Western listeners as they did not have a lifetime of musical memories to draw on… but they were significantly above chance. In other words they recognised the basic emotions in a completely novel musical form.

Over 2000 years on from Plato on we have some evidence that music’s communication of emotion is so powerful it can cross cultures. It speaks to something quintessentially human in all of us.

**NOTE – Next week I will be blogging about a new DVD course on music psychology, which includes excellent lectures on music & emotion. Stay tuned!**

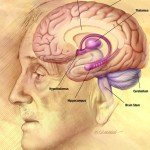

Music’s command of emotion helps it drive deep powerful memories. There are superhighway brain structures that link hubs of emotion and memory processing. This explains why we may struggle to remember this time last week but can clearly recall emotional memories from decades past.

Music’s command of emotion helps it drive deep powerful memories. There are superhighway brain structures that link hubs of emotion and memory processing. This explains why we may struggle to remember this time last week but can clearly recall emotional memories from decades past.

Musical memories are no exception – those with emotional traits are often the strongest and the longest lasting.

And because of the emotional character of so much of our music, this means musical memories are more likely than most other forms of memory to be strong.

Indeed, the link between music and emotion helps in part explain why our musical memories often survive when general memory begins to fail either through injury or through disease, such as in the case with dementia.

Recent research from my own lab, ‘Music and Wellbeing at the University of Sheffield’ and Lost Chord, has revealed a multitude of responses to live music as part of dementia care. We see great potential in capturing the unique power of music in memory to support lifelong wellbeing.

So what piece are we going to end our concert with today to illustrate the emotion in music? As you might imagine I was not short of ideas. But in the end I chose a movement from Brahms’s Clarinet Trio.

One of four clarinet chamber works composed by Brahms in rapid succession after he emerged from retirement toward the end of his life, the piece was inspired by the skills of Richard Mühlfeld, a gifted clarinettist of whom Brahms became personally fond, referring to him as “my dear nightingale”.

Ironically, given our discussion of Plato and musical emotion, the painter Adolf Menzel. on hearing Mühlfeld’s playing at the premier, sketched the clarinettist as a Greek god. He sent the drawing to Brahms with the following note:

Ironically, given our discussion of Plato and musical emotion, the painter Adolf Menzel. on hearing Mühlfeld’s playing at the premier, sketched the clarinettist as a Greek god. He sent the drawing to Brahms with the following note:

“We confess our suspicions that on a certain night the Muse itself appeared in person (disguised in the evening dress of the Meiningen Court) for the purpose of executing a certain woodwind part. On this page I have tried to capture the sublime vision.”

So, to play the deceptively simply but gloriously intimate Adagio from Brahms’s Clarinet Trio in A minor, please welcome for the last time principal players of Aurora Orchestra: James Burke, clarinet, Oliver Coates, cello, and pianist John Reid.