Why Music? Memory and Melody

Dear Reader,

From 25th- 27th September I had the honour of being one of Radio 3’s resident experts for their Why Music? Weekend.

From 25th- 27th September I had the honour of being one of Radio 3’s resident experts for their Why Music? Weekend.

What a fantastic event it was, held in London’s Wellcome Collection. Alongside Philip Ball (author of The Music Instinct) I contributed to a number of the live programmes including Why Music? Question Time and Why Music? Round Up both presented by Tom Service.

A few months ago a fantastic Radio 3 producer called David Papp asked me if I would design a concert for the weekend with the support of principle players from Aurora Orchestra

The aim of the concert was to explore why music is so powerful in memory. I decided to use the 90 minutes to speak on 4 different reasons why music is powerful in memory. For the next 4 blogs I will present for you, Dear Reader, the script that I wrote for this concert. Starting with reason 1 – Melody. I hope you enjoy.

Radio 3 – The story of Music and Memory: Melody

Welcome to the Reading Room. For the next ninety minutes, we’ll be discovering the unique power of music in memory — how music itself creates strong memories over time; how its multifaceted nature makes it a powerful stimulant for wider memory processes; how musical structure reflects a natural ‘developmental’ flow going from the aspects of music we experience and understand first (yes, even as a foetus!) through to how we learn about music as a child and an adult, and finally to consider what music comes to mean to us as a listener.

Joining us on this musical journey into memory are Beethoven with his set of variations on one of Mozart’s best knownarias, César Franck – his Violin Sonata, Igor Stravinsky with his Suite from The Soldier’s Tale, and Brahms’ Adagio from the Clarinet Trio. And joining us to perform the music are principal players of Aurora Orchestra: James Burke, clarinet, Alexandra Wood violin, cellist Oliver Coates and pianist John Reid.

To begin,I am going to explore how the very elements of music itself, its ingredients, make it such a powerful agent within our memory: starting with melody. The majority of the world’s music revolves around melody. All known musical cultures, throughout history, have delighted in compositions that present a beautifully shaped pattern of notes that evolve over time and timbre.

Arthur Schopenhauer once said ‘Music is the melody whose text is the world’.

You as a listener have been captivated by melody since before you were born. A foetus in utero with a typically functioning auditory system begins to sense and respond to patterns in sound during the second trimester, around 5-6 months into a pregnancy.

Our foetal young get a peculiar experience of this first auditory world, surrounded as they are by fluid. Two important aspects of music are easily transmitted thought this medium; the rhythms of the inner and outer world, and its melodies.

Our foetal young get a peculiar experience of this first auditory world, surrounded as they are by fluid. Two important aspects of music are easily transmitted thought this medium; the rhythms of the inner and outer world, and its melodies.

In fact, a foetus’ world is a great deal more melodic than we realise – without the details of sound, those fine high frequencies that are absorbed by amniotic fluid, the foetus gets to the heart of melodies – the contours of sounds: both musical and environmental.

A car engine is a melody; a plane taking off is a melody; their mother’s voice is a melody; a lullaby is a melody.

All these melodies have an impact on our pre-term children, as studies now show that they can recognise melodies heard in the womb after they are born. These are their first musical memories.

Even more astonishingly, babies are already using their memory for melody in their first cries. A study by Birgit Mampe and colleagues found that while French babies cry with the melody of French verbal intonation, German babies cry with the opposite melody of German intonation.

Clearly, melody sticks in memory right from the start and one reason appears to be that we need to be able to replicate the melodies of our world more or less as soon as we arrive. The attraction to melody we see in our new-born young is entwined with their fascination for the human voice. Babies are captivated by the exaggerated melodic sweeps of our spontaneous infant direct speech – the sing-song way we all talk to babies. Studies show that this kind of speech is both more attractive and soothing to infants compared to the way we speak to fellow adults.

Taking all this information into account, it should come as no surprise that it is melody that forms the strongest basis of our first musical memories. Our instinct and our need for replication, for song, as we communicate and learn. It is the melody of music that sticks with us, the songs that we sing in our minds as well as out loud.

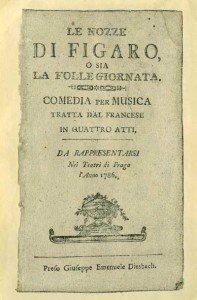

Great composers were and are fascinated by melody and in particular the way that a melody sticks in our memories. Mozart wrote a letter to his father in 1786 after the first performances of the Marriage of Figaro, sayinghow thrilled he was that every errand boy whistled his melodies.

Great composers were and are fascinated by melody and in particular the way that a melody sticks in our memories. Mozart wrote a letter to his father in 1786 after the first performances of the Marriage of Figaro, sayinghow thrilled he was that every errand boy whistled his melodies.

The Irish tenor Michael Kelly, who knew Mozart well, quoted him as saying: – Melody is the essence of music. I compare a good melodist to a fine racer, and counterpointists to a hack post-horse

I would love to be able to tell Mozart that he had a valid if not controversial point, as he had recognised the first key to our musical memories, creating melodies we can replicate in our mind’s ear, allowing us to enjoy his music in our inner world. But on some level, I’m sure he knew that already!

A good melody sticks in our memories because we enjoy replicating it as we have done since the moment we were born. Replication being amongst the most sincere forms of flattery.

In our first introduction to the power of music in memory, we will hear Beethoven’s homage to one of Mozart’s inspired melodies from The Marriage of Figaro, ‘Se vuol ballare’.

Sung by Figaro himself in the first act of the opera, I am sure you will find it hard – just as Mozart intended – if not impossible, to resist singing along in your mind’s voice, drawing on those long standing and powerful musical memories.

When you recognise the melody take a note of how Beethoven indulges in variation of that powerful musical contour. The importance for memory of this technique and other deep musical structures will be the subject of our next section.

So please welcome violinist Alexandra Wood and pianist John Reid to play Beethoven’s Variations on ‘Se vuol ballare’ from Mozart’s ‘The Marriage of Figaro’… Beethoven Variations on ‘Se vuol ballare‘ from Mozart’s ‘Figaro’ in F major O.40 (pf, vn)

A recording of these variations by other artists can be heard here – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dhv9a6xHY1I

5 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback: