SMPC Day 3: Session 3 (Evolution)

Don’t ask me why, but I fancied carrot cake for lunch on Saturday. I was not really hungry enough for a meal but I wanted to keep trying new food here in Canada and although I like carrot cake in the UK I was reliably informed that it was better here. This turned out to be true! I returned to the conference on a sugar high, having consumed one of my five a day (no, really…)

Don’t ask me why, but I fancied carrot cake for lunch on Saturday. I was not really hungry enough for a meal but I wanted to keep trying new food here in Canada and although I like carrot cake in the UK I was reliably informed that it was better here. This turned out to be true! I returned to the conference on a sugar high, having consumed one of my five a day (no, really…)

The afternoon session of Saturday featured a session on evolution. The subject of music as evolution has proved very popular in recent years following the discovery of bone flutes aged to around 35,000 years ago in caves in Germany back in 2009. This was followed by studies of musicality in animals that featured, among others, the star that is Snowball the Cockatoo (and his similarly well known but never seen to dance colleague, Ani Patel)

Is there really any evidence for the evolution of music? Henkjan Honing broke this question down in a really interesting way and one that opened my eyes to another way to organise our thoughts in this area. We need to ask the following; is there evolution of:

Is there really any evidence for the evolution of music? Henkjan Honing broke this question down in a really interesting way and one that opened my eyes to another way to organise our thoughts in this area. We need to ask the following; is there evolution of:

1) music, 2) music cognition and/or 3) musicality.

Accoring to Henkjan the answers are: 1) no, 2) no and, 3) maybe

The point is he made was that by the standards of evolutionary psychology we can’t ever know how music evolved as we don’t have the evidence (i.e. fossils). Furthermore, we can’t ever know about the evolution of cognitive traits. Evolutionary analysis cannot uncover HOW an animal achieved a particular feat – it is like looking at the surface of a car and claiming to know why, mechanistically, it goes so fast.

So the idea is to dispose of the pressure to explain questions 1) and 2) – that leaves you with something you can look at…musicality: The behaviour; a natural and spontaneously developing trait that is based on and constrained by our biological and cognitive systems. As opposed to “music”, a social and cultural construct – what I say is music might be different to your idea of music.

So the idea is to dispose of the pressure to explain questions 1) and 2) – that leaves you with something you can look at…musicality: The behaviour; a natural and spontaneously developing trait that is based on and constrained by our biological and cognitive systems. As opposed to “music”, a social and cultural construct – what I say is music might be different to your idea of music.

Try that thought on for size and see if it shifts your perspective in the way it has mine.

Now the challenge is to look at musicality and drill down into what that word actually means. What behaviours comprise musicality? Once we have those then we can identify the mechanisms behind them and derive ways to probe them in animals, for example, therefore helping us to extrapolate an answer to the fundamental question, what makes us such a musical animal?

Next on was Meagan Curtis (Purchase College, USA). Now, speaking after Henkjan would be my idea of a nightmare. Like when Jerry Lee Lewis allegedly set fire to his piano on stage at the end of his set walked into the wings to the lead act and said “Follow that”. But Meagan did a wonderful job with her 4 studies looking at evidence for sexual selection in music.

Meagan outlined the idea that sexual selection promotes traits that are beneficial for reproduction (as opposed to survival, the drive in natural selection). Sexually selected traits offer fitness indicators regarding the genetic qualities of the individual. For example, the peacock’s tail. Might music fall under this category for humans?

Meagan outlined the idea that sexual selection promotes traits that are beneficial for reproduction (as opposed to survival, the drive in natural selection). Sexually selected traits offer fitness indicators regarding the genetic qualities of the individual. For example, the peacock’s tail. Might music fall under this category for humans?

There are a few things we have to achieve in order to make the argument that music performance is a candidate for sexual selection. The “Holy Grail” as Meagan put it, would be genetic markers and we don’t have that yet. But in their absence we can look for evidence of a reproductive advantage and a behavioural preference for musicians, when all other things are equal.

In her first study Meagan asked 300 students questions about their parents musicality and about their number of offspring.

Turns out that higher musicality predicts more offspring in males but not females,. This sexual diamorphism is along the lines of what we see in nature as well, with the males (as in the peacock) being the ones whose displays are related to reproductive success.

In her second study she asked people directly about the number of ‘reproductive opportunities’ they had in the past (hem, hem) and about their musicality. Same result – a relationship in males but not females.

Here we have a bit of evidence for the reproductive advantage for male musicians. How about actual behavioural preferences? Do women prefer a musician, as compared to a comedian or a semi-pro video gamer? Meagan designed an online dating paradigm to test this question and turns out that 54% prefer the musician, 27% prefer the comedian while only 19% go for the gamer.

Finally, she asked about the mechanisms behind all these correlations and selections. Does being a musician actually translate as a fitness indicator, something that tells women about the genetic quality of the male in front of them? In another online survey Meagan reported that women estimated musicians to be significantly smarter than the same image of someone who they were told was not a musician. A difference of about 5 IQ points.

All this evidence suggests that music may currently be playing a role in mate selection – the Holy Grail of genetics is needed if we are to stretch this into an evolutionary argument.

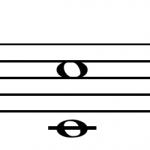

Finally, we heard a talk by Marisa Hoeschele (University of Alberta, USA). Her research question concerned octave generalization, the idea that we perceive some level of similarity across the same note in different octaves. This relationship is quite unique and it apparently occurs a lot in the natural world too.

Marisa was interested in looking at octave generalization from a comparative perspective – do you find it in animals? She has started with a charming little bird called the Black Capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) mainly because it is a vocal learner (like you and me) and it has a good sense of pitch.

Marisa was interested in looking at octave generalization from a comparative perspective – do you find it in animals? She has started with a charming little bird called the Black Capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) mainly because it is a vocal learner (like you and me) and it has a good sense of pitch.

The birds were trained to respond to certain notes within octave 4 and then their generalization was tested by presenting the same notes in octave 5. A nicely similar paradigm was developed for humans, though this involved only verbal feedback during training instead of feedback in the form of a nice tray of seeds.

Marisa found that humans were able to react to octave generalization, even in complex reversed conditions, but the birds were not. The birds learned the response in octave 4 well but did not apply this response to the same notes in octave 5. This evidence points towards different pitch perception mechanisms in birds and us, and Marisa suggested that maybe these birds lack a pitch chroma.

Marisa found that humans were able to react to octave generalization, even in complex reversed conditions, but the birds were not. The birds learned the response in octave 4 well but did not apply this response to the same notes in octave 5. This evidence points towards different pitch perception mechanisms in birds and us, and Marisa suggested that maybe these birds lack a pitch chroma.

More interesting work will I am sure now follow in other species, and also trying different octave ranges to make sure the effect is valid.

A long blog for you here but I hope you will agree some really fascinating ideas and research. Looks like our research in the field of music and evolution is about to shift gears but then that is always the best way with science. Always evolving… (love a little pun now and again)

3 Comments

Aaron Wolf

I see how any evidence is something, but this is extremely hard to tease apart here.

When asking about reproduction and opportunities for musicians, especially those old enough to have grown children, we are talking about people in certain cultures and times. The career of professional musicians in pop styles involves travel and thus meeting more people, and it is also tied to alcohol consumption, and and and and etc. And that may culturally be different for men and women. How can this possibly be accounted for?

When comparing to birds, how can we possibly find the right human control: a person with normal competence (not amusic) who has never been exposed to cultural contexts and learning in which octave-similarity was reinforced? Maybe the better test than the one described here would be to see if octave similarity can be taught to chickadees effectively enough that they learn to generalize it…

Thanks for the write-up, interesting stuff indeed. It does seem like grasping at evidence that may be just too far out of reach to really discover.

Mark Riggle

Meagan’s research mostly confirms that, because of the strong pleasures in music, sex-selection by female choice is occurring. Given the way female-choice sex-selection works, this is expected for music. However, because sex-selection is currently operating for music does not mean that music is a fitness indicator; if it were, then because music is a very expensive trait (the pleasures cause us to expend large resources for it), sex-dimorphisms would be apparent, and they are not. Therefore, music cannot be functioning as a fitness indicator (as neither a direct nor indirect fitness indicator). The options for how music can be sex-selected but not be sex-dimorphic are few (and perhaps really only one option).

What this sex-selection on music also means is that whatever traits can contribute to creating more pleasurable music (pleasurable to a target audience) will be selected for and be amplified by that selection. This amplification of a trait would have been occurring in the distant past and, critically, would still be occurring. What traits can contribute to creating more pleasurable music? There are many (think about the music cognitive rules system for example), and this, I think, gets to the heart of what Henkjan wants for the evolution of musicality.

The sex-selection for musicality does mean that at some point in time, sex-dimorphisms will emerge; that is, the musicality traits must continue to develop and amplify. The mechanism (that option above) which is keeping the sex-dimorphisms from emerging will reach a limit in the traits (where for females the costs exceed the benefits) and then sex-dimorphism will occur in them. Right now, we must still be in the mechanism’s sweet-zone.

Mark Riggle

At the risk of touching the third-rail of sexual politics and having no one read it, I have to add this.

Pleasure from music seems to really consist of a collection of pleasures. Those various sub-types of music pleasure very likely do display some sex-dimorphisms. Although individual variation of them will be great, the ‘average’ pleasures should be expected to be sex-dimorphic based on the prior sex-selections for music. The music sub-pleasures that are important here are: 1) the listening pleasure where the anticipation of the music provides the pleasure (for example in Huron); 2) the pleasure of novel music; and 3) the pleasure of inventing new music (mentally imagined or physically realized). While they are all related, the distinctions between the music pleasures seems reasonable. The total music pleasure does have a limit — it cannot exceed the pleasure of food or sex, but also as David Huron has observed, it is pretty close. However, the amount of pleasure from each subtype will be different for the sexes.

To understand this point, look at the poster child for sex-selection, the peacock (the male) and the peahen (the female). The peacock expresses the genes that create a large tail, but the peahen must express the genes that make the visual display of the male’s tail pleasurable. It is that pleasure that attracts the peahen to the peacock. The better the tail, the more pleasure. In the peahen, that is called the preference trait — the visual pleasure from big tails. That trait, just like the tail expressing trait in males, must be sex-dimorphic. The males will be disadvantaged if they are attracted to the large tails of other males, hence, they must not express that preference trait. That peahen pleasure is analogous to the first and second music pleasures for humans, but fortunately, only the relative pleasures need to be changed, not eliminated.

Those subtype music pleasures will each motivate different behaviors; those behaviors that will produce the pleasures. It is those different and costly behaviors that will affect the individual’s fitness or reproductive outcome. In females, that first listening pleasure and some of the novel music pleasure (the 2nd pleasure) are what will cause the sex-selection to occur; it will select for males that provide more pleasurable music. For males, more of the second music pleasure (causing the seeking of novel music to learn from) and the third pleasure (invention) will both influence the display of music which should stimulate the first subtype pleasures in females.

The upshot of that analysis is the expectation that males receive less pleasure from listening to music than females receive. Males, however, should (on average) receive greater pleasure from more novel (or even strange) music and also more pleasure from inventing music. The caveat is that there is large variations in individuals, so this would be an average. And lastly, unlike the peacock world, the music pleasure is not the only determiner of reproductive success for males. There are many avenues for making pleasurable environments besides music — personally, I thank heaven for that.

Ok, ouch, that third-rail will hurt.