Musical chills are in the eye of the beholder

Afternoon Dear Reader,

It’s a rather grey and dull late October day here in York, but mild and dry at least for the time of year. The lack of rain bodes well for the York Illumination Festival which is attracting a lot of well deserved attention in my home town. The festival happens every year now and has one main aim – to show our wonderful city off in a whole new ‘light’.

It’s a rather grey and dull late October day here in York, but mild and dry at least for the time of year. The lack of rain bodes well for the York Illumination Festival which is attracting a lot of well deserved attention in my home town. The festival happens every year now and has one main aim – to show our wonderful city off in a whole new ‘light’.

This evening my dear husband and I plan on taking a walk to enjoy the streets in their temporary multicoloured overcoat. We might even treat ourselves at the fresh doughnut wagon! A jolly plan to banish coming winter blues.

A stunning piece of visual art or music has the potential to give the lucky consumer a case of the ‘chills’. This peak emotional experience is marked by shivers down the spine and along the extremities, the hairs standing on the back of the neck, bumps on the skin (in his native Spanish my husband calls this reaction ‘chicken skin’, which I love), a dry mouth and a racing heart. These are all physical manifestations of a deep psychological experience of pleasure, triggered by activity of neurotransmitters such as dopamine being released deep within ancient survival centres of the brain.

Not everyone gets chills however, people who do report that the experience is consistent to the same music over long periods of time. In a recent class I was asked by a student if there was any evidence that the brain response could be exhausted by listening to the music over and over again; in effect, can you kill a chill? I don’t think that has ever been tested, but given that the music pieces that trigger chills tend to be favourites for each listener we can assume they have heard them many times over the course of their life and yet the chill response continues.

There is also scientific evidence from the animal kingdom that reward responses of this kind don’t tend to satiate over the long term. A rat who is given a lever to push that stimulates similar brain circuitry to that active during a chill experience in humans will press and press that lever at the expense of almost anything else, never seeming to tire of the experience.

I have written blogs on how chills experience happens and who gets chills the most, as and when new research has appeared. This week I found a new paper that adds a new physiological reality to the chills experience, a new measure that scientists can look at to see how this rare psychophysiological event impacts on our bodies.

I have written blogs on how chills experience happens and who gets chills the most, as and when new research has appeared. This week I found a new paper that adds a new physiological reality to the chills experience, a new measure that scientists can look at to see how this rare psychophysiological event impacts on our bodies.

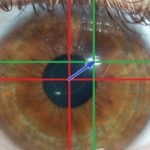

Researchers have been looking into our eyes….

The new paper is open source, published in ‘Consciousness and Cognition’ and is called Music chills: the eye pupil as a mirror to music’s soul.

The authors of the new paper were interested to find out if there was any relationship between the extent that our pupils become dilated and reports of musically induced chills. In their own words:

“…our present aim here was to determine whether pupil diameter, which has been little investigated in relation to music and, in particular, the occurrence of intense responses to music, can provide a particularly relevant and possibly universally-applicable measurement of intense emotional responses to music”

Changes in pupil diameter are an automatic body response so are not under our direct control. As such they are referred to as an ‘honest signal’ of our internal states. The interest is therefore in identifying another body signature of chills, but also in determining whether degree of pupil dilation might bear a relation to the degree of our emotional reaction to a piece music; testing the eye as a potential window to our deepest instant reactions to music. A fascinating idea.

Other than in response to changes in light, why do our pupils dilate and what does it really mean?

1 – Something has grabbed our attention. Our pupils dilate to indicate a special focus of our conscious minds. This has nothing to do with our reaction or the valence of the experience, just the grab.

As a journalist wrote in The Scientist (December 6, 2012): ‘‘What do an orgasm, a multiplication problem and a photo of a dead body have in common?”. It is a high and intensity level of attention processing at that point in time as compared to our normal mental tick over rate.

2 – Emotional/ aesthetic triggers. This has to do with the valence of our response, which goes beyond simply having your attention grabbed.

Our pupils dilate when we engage emotionally with an external stimulus (positive or negative) or an idea, and when we find something to be aesthetically pleasing.

The evolutionary reason for this response is thought to be partly linked to our fear/ startle response, when we instantly need to get a clearer picture of something that has triggered a fast emotional response. At these times the eyes open wide to allow us to monitor a larger visual field area.

3 – Neural/neurophysiological processing. An increase in brain activity, especially an increase in system connections, can also trigger pupil dilation. In particular, the authors of the present study point out that as well as the well explored dopamine system, music listening has been linked to activity within the locus coeruleus (LC), a brain hub for the production of the neuromodulator NorEpinephrine (NE).

The LC-NE system has been little studied in relation to music, but there are reasons to think that this system, alongside the dopamine pathways, may support the chill experience in music. And if the LC-NE system is involved then we would expect to see pupil dilation.

So there could be many reasons, and likely more than one, why our pupils might dilate in response to musical chills. We know the pupils dilate more when looking at increasing aesthetic beauty (paintings or fellow humans). But is the same true of musical chills?

Method

The 52 participants in this study (mean age = 31.98; range = 21–59: 28 female) were asked to provide 3 musical pieces that they believed reliably gave them chills. These pieces were played in the lab, via headphones, while participants kept their eyes open onto a blank grey screen and their gaze was monitored by an eye-tracker.

Funnily enough there was no overlap whatsoever in the chosen chill music – so the authors ended up with 156 pieces of chill music. That goes to show the importance of musical preferences and life experiences that lay behind why we get musical chills.

What genre were represented? It would be easier to ask which were not! The list included Blues, Jazz, Classical, Pop, Soul, Hip Hop, Rap, Funk, Folk, R&B, Rock, Metal, Punk, Indie, Folk, Ambient, Trance, Electronica…and so on…

In addition, the authors played 3 control songs to each participant (i.e., 3 songs selected by another of the participants, matched by sex and age) to assess how chills depend on musical preference more than on a person’s generic propensity to react intensively to musical stimuli.

There were two phases to the main part of the study where participants heard their own chill music. First they listened and indicated with button presses exactly when chills occurred (active condition). Then they listened again to the music without doing anything and pupil response was measured at the points known to trigger chills (passive condition). Hence the measure was taken in a pure listening situation rather than reflecting any requirement to push buttons.

The results

All but one participant got chills to their self selected music in the lab. And some people reported chills to their non-selected music (i.e. the chill music of other people).

All but one participant got chills to their self selected music in the lab. And some people reported chills to their non-selected music (i.e. the chill music of other people).

The frequency of chills was significantly and very much higher in the self-selected music condition, the difference being roughly an average of 1 chill to non-selected music vs. 8 chills to self-selected music.

33 participants data were analysed for the pupil measurements on the basis that they had a minimum of 3 chills in the study, so their responses could be averaged.

Measures were taken based on a two second window around the time that a chill was thought to be happening, according to the button presses in the earlier part of the trial.

At the moment of an intense emotional response, the point of a chill, pupils were larger than the typical pupil size to the whole song.

Pupils were also found to be significantly more dilated to chills from self-selected songs compared to chills triggered by non-self selected songs.

In another interesting finding pupil dilation reduced as the experiment went on, which suggests that although chill responses to the same song may not diminish over the long term, the chill response itself can be exhausted in the short term if you try to trigger it over and over again in the space of a few minutes.

Take aways

“We found that the eye pupil diameter mirrors intense responses to music” – indeed they did, and it was interesting to see that this response is sensitive enough to pick up stronger and weaker chills (based on self-selected vs. non self-selected chill experiences) and is so automatic that it can be picked up in a passive listening condition, where the participant is not responding in any way to the chill they feel.

The authors speculate that their data supports the relatively new idea that musical chills stimulate not only the dopamine system, but also the engagement of the LC-NE system. This system is associated with the functional interaction of diverse brain systems (as we know is necessary in music processing) and focused attention.

The authors speculate that their data supports the relatively new idea that musical chills stimulate not only the dopamine system, but also the engagement of the LC-NE system. This system is associated with the functional interaction of diverse brain systems (as we know is necessary in music processing) and focused attention.

In pupillometry we researchers now have a new objective way to determine the basic occurrence of musical chills – a method that is a lot cheaper and less time consuming than brain imaging techniques! Not only this, but this research has opened new theories as to why chills happen, implicating wider brain systems than simply reward.