Music for stress reduction – social context matters

Dear Reader,

I am back from summer holidays. Gosh – that was needed! I had a lovely break, spending time with family and friends, doing jobs arond the house, and visiting the beautiful city of Florence for the first time.

Rest and relaxation of the kind I have experienced in the past couple of weeks is so important for the mind, but also the body. It is easy forget that your body can become tired when your job is largely sitting down all day. This situation puts pressure on the legs and spine, as well as reducing the bodies ability to flush out toxins. I needed time to take regular exercise and eat well – and I am feeling much better for it 🙂

I hope you enjoyed a nice summer, Dear Reader. Autumn is fast coming upon us and a new academic year will soon begin. Life at my University is starting to kick into high gear once again and our thoughts are turning to the fresh and hopeful faces that will soon arrive for their undergrad and postgrad degree training. We look forward to meeting you all!

Before the new term strikes I wanted to touch base and tell you about a nice paper I read recently by Linnemann et al. that connects to my research on Music and Wellbeing. Many people are interested in the psycho-biological effects of music – how music impacts on our body systems that then cascades towards a psychological response. In the present case of interest, the brain body chain reaction of interest relates to stress.

Stress, as we all know, is a good thing in the short-term (it helps keep us out of danger) but a bad thing in the long term (it wears us down).

Stress reactions are associated with a basic body response we call ‘fight or flight’.

When faced with a perceived threat, real or imagined, the brain increases production of stress hormones that impact our body states (heart rate, blood pressure, digestion) and how we feel.

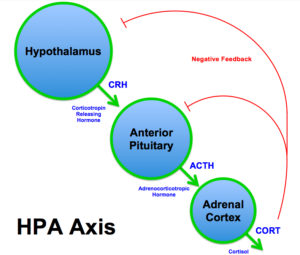

One key brain regulation system involved in this process is the hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis can be measured indirectly by tracking level of cortisol. Lots of cortisol = lots of HPA activity = the experience of stress.

Many studies have shown that music is associated with HPA axis activity, as it can both increase and decrease cortisol levels.

Another stress marker is an enzyme found in our saliva called alpha-amylase. One study showed that listening to music prior to a stress trigger was associated with faster recovery, as measured by alpha-amylase levels, compared to a non-music condition.

Whilst we know that music can impact on our stress experience, as measured by cortisol and alpha amylase, there has been little investigation into the context of these effects. A new study sought to refine our knowledge by asking about the effects of different social contexts on these effects.

Whilst we know that music can impact on our stress experience, as measured by cortisol and alpha amylase, there has been little investigation into the context of these effects. A new study sought to refine our knowledge by asking about the effects of different social contexts on these effects.

Most studies in this area of literature have looked at the effects of inidividual music listening, a lot of the time using headphones. There are some studies of stress responses as part of group music making (e.g. singing, drumming), but these compound activity and listening so the pure effect of a social setting on music listening cannot be attributed.

This is a rather surprising gap in the literature, since many impacts of music are associated with social context, for example feelings of belonging (linked to wellbeing) and social cohesion. Having a place in the world. There are also benefits of music listening when that music brings up thoughts of other people.

Hypotheses

The presence of others while listening to music will enhance the stress-reducing effect of listening to music.

The familiarity of people will modulate this effect – greater attenuation of stress is predicted when people are surrounded by friends as opposed to strangers.

The Test

The authors tested 53 healthy young adults as part of their regular daily routine, to give the study that all important real world feel (high ecological validity).

Participants were provided with a pre-programmed iPod Touch, which they were asked to carry with them for 7 days. There were 4 main assessments each day after an initial morning prompt (11am, 2pm, 6pm and 9pm) where people reported their data using the Touch. They reported whether music listening had occured since the last prompt and if so the social context, i.e. the presence of others and their familiarity. Reasons for music listening were also reported and happiness of the music was ranked. The volunteers collected their own saliva samples at each prompt for later analysis of both cortisol and alpha amylase.

Results

Statistical models were created to investigate the relationships between the control variables (gender, social context, control over music choice) and the outcome variables (subjective stress level (self report), cortisol, alpha amylase), as well as the predicted impact of familiarity in social context.

Music listening was reported at 38.5% of the prompts over the 7 days.

Of those episodes, 35% occured in the presence of others, more often with friends (64.3%) than strangers (35.7%)

Overall stress level was at an average self-report figure of 1.25; the average was 1.27 when alone vs. 1.04 in the presence of others. This main effect, a reduced reported level of stress in a social context, was statistically significant. This result makes intuitive sense as many stressful situations occur when we are alone (e.g. at work) and can’t interact with others. But does music enhance the stress reducing effects associated with social situations?

The models suggest yes. There was an interaction between the level of stress reported in the presence of others vs. the presence of others while listening to music, meaning listening to music had a significant additional and unique effect in social situations that can’t just be explained by the presence of others.

The presence of music in social situations also explained a small degree of unique reduction effect on levels of cortisol (2.25% additional variance for the geeks out there) and alpha amylase (2.91%)

However, the second hypothesis, that the familiarity of the people would matter, was not supported by the evidence. The presence of others enhanced the stress reducing impacts of music, but this effect was no bigger if those people were friends.

Interestingly the ‘music with others’ effect was also not related to the reported reason for music listening. It did not seem to matter whether or not the people intended to try to relax with music listening or were listening for another reason (e.g. just to fill the background).

Conclusions

The perceived and real (i.e. body based) relaxing effect of music are slightly enhanced in all social situations (not just familiar) compared to when we listen to music alone.

The authors of this paper suggest that this interesting finding is in line with the stress-buffering hypothesis of social support. Just the presence of others is enough to boost a relaxation effect, irrespective of any special task instructions or special relationships with those people.

One general idea to explain this result is that the presence of music can enhance the potential for feeling social connectedness and cohesion, and for positive emotional interactions. This is a state which we find relaxing. Seen in this light, music has an INDIRECT effect on our health, by virtue of it promoting a general social-related wellbeing mechanism. An interesting idea.

Would this social boost mechanism differ between music listening and music making? My particular interest in regards this paper is the use of live music as an activity in care homes. Here the evidence to date suggests that both music listening and music making are associated with positive effects on emotional state and social interactions, as long as the activities are group based rather than conducted in isolation. It is possible therefore that at least some of the ‘music with others’ stress reducing effect reported here is common to all musical situations.

The real world context of this study is especially interesting as well. So much of what we know about the stress reducing effects of music comes from lab studies, which have the advantage of being better controlled and balanced, but lack the ecological validity – the confidence that the brain and body would really react this way out of an unfamiliar lab setting.

Overall, this is a well conducted study with an intriguing story to tell. We often dismiss music listening as a background activity that, while pleasant, has little real measurable effect on our big body and brain systems – you need to get active in music making to get those big effects. I still believe that the effects of simple music listening on systems like the stress-monitoring HPA axis are fairly small and variable, however, it is thought provoking to consider that the presence of others might enhance the positive effects that music listening can have on our perceived stress levels.

Link to the paper: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27393906