Music, emotion and the brain

Hello Dear Reader

This week has been one of the busiest of my life. I sold my London flat, bought a house back in my wonderful home town of York, and of course published my baby.

You Are The Music was very briefly the number one selling music book on Amazon last week, a fact that still astonishes and humbles me. I really enjoy the idea that I am making a contribution to music, however small.

I have rarely been so proud and grateful in my life: thank you, Dear Reader.

Now that the book is out there in the big wide world I am starting to hear what people think of it. That is, people other than my family and publisher, two rather biased sources of feedback. So far the word is good, there have been some kind and thoughtful reviews for which I am eternally grateful.

To be honest, I am more sensitive than I had assumed to these reviews: it’s funny how deeply you can feel towards what amounts to a pile of paper and words about music.

Speaking of deep emotion connections to music, I have just finished a cracking review on research into the brain correlates of music-evoked emotions by Stefan Koelsch and published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

The subject of music and emotions is one of the most heavily researched in the field of music psychology. This is not too surprising as it plays to a core question for our discipline – why does music change the way that we feel? Koelsch’s new article filters and frames decades of brain research in this area in an easily digestible and, in many places, surprising summary.

Koelsch first talks about the earliest (i.e. most primitive) brain origins of music evoked emotions. As soon as music hits the ear it stimulates spinal motor neurons and vestibular, visceral systems.

Koelsch first talks about the earliest (i.e. most primitive) brain origins of music evoked emotions. As soon as music hits the ear it stimulates spinal motor neurons and vestibular, visceral systems.

These activations are responsible for some of the arousing effects of music and may also contribute to the feeling we get that when music makes us want to ‘move to the beat’.

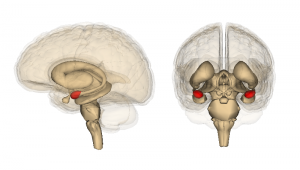

Next, Koelsch talks about the core emotion brain network and focuses down on three main candidates: the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens and the hippocampus.

The amydala (from the Greek amygdale, ‘almond’) is a deep, central brain structure that receives some of the first projections from the lower brain centres. Music stimulates the amydala in a similar way to faces, smells and other sounds, most likely because all these stimuli are perceived as having social significance due to their communicative properties.

The amydala (from the Greek amygdale, ‘almond’) is a deep, central brain structure that receives some of the first projections from the lower brain centres. Music stimulates the amydala in a similar way to faces, smells and other sounds, most likely because all these stimuli are perceived as having social significance due to their communicative properties.

According to Koelsch the amygdala is part of a larger network that regulates approach-withdrawal behaviour in response to socio-affective cues, including those given by music.

Finally, the amygdala likely has a role in how we evaluate and learn about positive as well as negative stimuli and therefore is involved in how our behaviour eventually becomes reinforced towards or away from certain musical sounds.

Next, the nucleus accumbens (NA). The NA is well known to be activated by peak emotional experiences, known as chills or frisson but it is also activated as soon as music is experienced as pleasurable. In general the NA is sensitive to primary rewards (food, sex) and secondary rewards (money, power), so it represents hedonic value for us and helps to initiate behaviors that aim to obtain more of these rewards for consumption.

Next, the nucleus accumbens (NA). The NA is well known to be activated by peak emotional experiences, known as chills or frisson but it is also activated as soon as music is experienced as pleasurable. In general the NA is sensitive to primary rewards (food, sex) and secondary rewards (money, power), so it represents hedonic value for us and helps to initiate behaviors that aim to obtain more of these rewards for consumption.

This finding suggests that music can be a very rewarding emotional stimulus: a fact that few music lovers would doubt. The NA activation signals the anticipation of the rewarding experience of hearing pleasurable music, as well as the actual experience of enjoying the music. It also has a role in predicting whether we go on to acquire the track for ourselves.

Finally, Koelsch moves on to the hippocampus (from the Greek hippos meaning “horse” and kampos meaning “sea monster” – it looks like a little seahorse!) Now, here is a brain structure that I thought I knew quite well because it is so involved in memory (my main research interest).

Finally, Koelsch moves on to the hippocampus (from the Greek hippos meaning “horse” and kampos meaning “sea monster” – it looks like a little seahorse!) Now, here is a brain structure that I thought I knew quite well because it is so involved in memory (my main research interest).

But I learned new things about the hippocampus from this article.

Firstly, I learned that the hippocampus is connected to our emotional reactions via its involvement in the regulation of our brain’s chemical stress response, which comprises the hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal glands all acting in synchrony. The hippocampus is implicated in music-evoked positive emotions that can, in effect, pacify this system, reducing the release of stress hormones like cortisol.

Apparently the hippocampus is quite sensitive to chronic levels of these kinds of stress hormones in general and long term exposure, for example in some cases of PTSD and depression, can damage the neurons in this brain structure. This damage may have consequences for the way that someone reacts to positive stimuli as well as their sensitivity to levels of oxytocin, a neurochemical that promotes social bonding.

The fact that the hippocampus reacts to emotional music (including fear and joy) suggests that it is responsive to the potential of music to stimulate the release of brain chemicals that affect its function, by virtue of that music’s emotional associations and core meaning.

The article then goes on to support the role of these three structures (the amygdala, the nucleus accumbens and the hippocampus) in emotional regulation by citing studies of patients with brain lesions in those areas. Lesions or degenerative damage in these areas can impair the ability to perceive or react to emotion in music.

How does music actually evoke emotion?

How does music actually evoke emotion?

Of course there is the debate surrounding whether music really stimulates actual emotions, but Koelsch argues that it does (at least in part) because musical emotions have all the signs of ‘real’ emotions including bodily reactions, facial expressions, and action responses (such as dancing, singing, and crying).

So if we assume that at least some musical emotions are the genuine article, how does music make us feel this way?

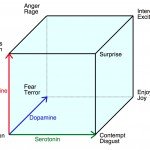

Koelsch identifies four sources within music itself (i.e. not its memory associations) that can trigger emotional reactions : 1) acoustic factors (e.g. consonance/dissonance, loudness); 2) structural stability (e.g. moving to and from the tonal centre); 3) the extent of structural content in the music; and 4) structural breaches.

Therefore, one of the sources of emotion in music relates strongly to our responses to any sound (number 1) while the other three are down to the way that composers play with the structure within music as it progresses, creating an ebb and flow of tension and relaxation, that in the right quantities provide the recipes for different emotional reactions.

Therefore, one of the sources of emotion in music relates strongly to our responses to any sound (number 1) while the other three are down to the way that composers play with the structure within music as it progresses, creating an ebb and flow of tension and relaxation, that in the right quantities provide the recipes for different emotional reactions.

Another interesting source of emotion is referred to as ‘contagion’: The idea that once an emotion is triggered, we experience the physiological manifestations of that state – so, for example, we might smile. That smile then feeds back into the system and reinforces the happy emotion that we feel.

Koelsch finishes the article with a few words about the potential of the emotional power of music to have measurable effects when applied in therapeutic/ medicinal settings. The key is evidence that music can change activity in brain structures that might otherwise be damaged in conditions such as PTSD, depression, and dementia. We have yet to know whether music has a strong enough effect to ameliorate the brain basis of some of these conditions and therefore reduce the symptoms, but the theoretical potential is there.

Koelsch finishes the article with a few words about the potential of the emotional power of music to have measurable effects when applied in therapeutic/ medicinal settings. The key is evidence that music can change activity in brain structures that might otherwise be damaged in conditions such as PTSD, depression, and dementia. We have yet to know whether music has a strong enough effect to ameliorate the brain basis of some of these conditions and therefore reduce the symptoms, but the theoretical potential is there.

Click here for a previous blog about the power of music and memory that features Henry, the man in the image above.

In sum, this detailed and well researched article provides an excellent overview of the ways in which music can evoke activity in core areas of the brain that underlie our experience of emotion, and outlines some of the ways in which the music itself can trigger these changes.

With this wealth of evidence in the bag it is now time to broaden the horizons in this field and move into lesser explored territories such as music and emotion in children and ageing populations, as well as the above mentioned exciting possibilities for therapy/medicine.

13 Comments

Diana Hereld

Thanks so much for sharing this. Music and emotion specifically remain my primary passion, and this brought some new info to light for me! It was interesting, when I asked Isabelle Peretz and the Peabody conference where the future hope of using music and emotion to bring hope to mental health healing lay, she simply answered “Data,” and explained that the theories are there, the research is getting there, but we need more experiments being carried out on greater populations to really generate the data and move forward. This makes sense to me, because although (for example) music therapists are making leaps and bounds (and changing lives) daily in behavioral analysis via anecdotal documentation, there’s still a such a small amount of empirical research comparatively. I’m so anxious to see where it goes from here. Cheers again!

Diana

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback:

Binny

Great description of the music in the relation of the brain..Of course some people do not have idea about this..By reading this article the idea gets clear about how it affects our brain….thanks for sharing..!!!!!

Pingback:

Pingback:

Philip Dorrell

Vicky, I have developed the hypothesis that the primary function of music is to trigger an altered state of mind that intensifies the emotions of daydreams, which I explain in more detail at http://whatismusic.info/blog/MusicAndDayDreaming.html.

On the one hand, the scientific study of music does not seem to have paid any special attention so far to daydreams. On the other hand, in the world of compulsive (“maladaptive”) daydreamers, the strong connection between music and daydreaming sees to be self-evident.

Pingback:

Keeping my name a secret :)

Hello! I’m using your article as a reference for a school newspaper on how music affects us emotionally. Hope you don’t mind, and I will tell that the website and information was gained from you. Thanks for writing this awesome article!!

Bernd Willimek

Music and Emotions

The most difficult problem in answering the question of how music creates emotions is likely to be the fact that assignments of musical elements and emotions can never be defined clearly. The solution of this problem is the Theory of Musical Equilibration. It says that music can’t convey any emotion at all, but merely volitional processes, with which the music listener identifies. Then in the process of identifying the volitional processes are colored with emotions. The same happens when we watch an exciting film and identify with the volitional processes of our favorite figures. Here, too, just the process of identification generates emotions.

Because this detour of emotions via volitional processes was not detected, also all music psychological and neurological experiments, to answer the question of the origin of the emotions in the music, failed.

But how music can convey volitional processes? These volitional processes have something to do with the phenomena which early music theorists called “lead”, “leading tone” or “striving effects”. If we reverse this musical phenomena in imagination into its opposite (not the sound wants to change – but the listener identifies with a will not to change the sound) we have found the contents of will, the music listener identifies with. In practice, everything becomes a bit more complicated, so that even more sophisticated volitional processes can be represented musically.

Further information is available via the free download of the e-book “Music and Emotion – the Research on Musical Equilibration:

http://www.willimekmusic.de/music-and-emotions.pdf

Enjoy reading

Bernd Willimek

Pingback: