Can neuroscience teach us anything about music?

Hello all

Apologies for my absence of late. I was recovering from a surprise dog bite to my right hand which made typing painful and slow. On the plus side I learned a valuable lesson: hands in the air around a dog! I shall be visually demonstrating absolute and total surrender to our canine companions for the near future.

Today I have been working on more earworm studies, after a day in and out of the media yesterday. Our group helped to make a documentary about the ‘tune in your head’ phenomenon (earworms) for BBC radio 4 over the last year and it was finally broadcast yesterday. You can catch a rerun here on the BBC Radio 4 website.

After a long morning of thinking about our new earworm paradigm I decided to take a look at a video link that I had been sent by the The Institute of Art and Ideas. According to their website the IAI is:

“committed to fostering a progressive and vibrant intellectual culture in the UK. We are a charitable, not-for-profit organisation engaged in changing the current cultural landscape through the pursuit and promotion of big ideas, boundary-pushing thinkers and challenging debates”.

The link they sent me seemed a suitably challenging concept. The talk is called ‘Neuroscience and the Mystery of Music‘. According to the preamble the talk challenges the ability of neuroscience to tell us anything about the nature of how our minds react to music. ‘Can neuroscience reveal the purpose of art? Raymond Tallis explains why our love for music remains beyond science’s grasp’.

The link they sent me seemed a suitably challenging concept. The talk is called ‘Neuroscience and the Mystery of Music‘. According to the preamble the talk challenges the ability of neuroscience to tell us anything about the nature of how our minds react to music. ‘Can neuroscience reveal the purpose of art? Raymond Tallis explains why our love for music remains beyond science’s grasp’.

Raymond was for many years a physician and a clinical neuroscientists and is very clear that he admires science, especially neuroscience, for the contributions it has made and continues to make for our world.

He takes issue however with the idea that neuroscience and evolutionary biology can explain the creation or appreciation of music, at least by using the current popular paradigms and arguments.

He first talks about brain activity during music perception and the idea that we can isolate neural activity in response to different constructs within music (timbre, pitch, rhythm). He takes issue with this kind of modular approach arguing that it bares no relation to the way we experience music – as a gestalt. Furthermore, whilst brain activity may be similar across different people our experience of perception can be vastly different, indeed within the same person over time. So what, if anything, is this kind of research actually telling us?

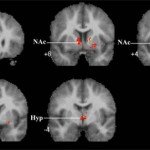

He then moves on to discuss brain activity associated with musical chills, and the famous study by Blood and Zatorre (2001). His argument is that in revealing that music activates the reward system, we actually reveal very little. There is no evidence, he claims, that neuroscience can distinguish between listening to favourite music and taking cocaine or having sex when it comes to the activity of the dopaminergic system. The neuroscience essentially tells us that we like the music – we knew that already.

He then moves on to discuss brain activity associated with musical chills, and the famous study by Blood and Zatorre (2001). His argument is that in revealing that music activates the reward system, we actually reveal very little. There is no evidence, he claims, that neuroscience can distinguish between listening to favourite music and taking cocaine or having sex when it comes to the activity of the dopaminergic system. The neuroscience essentially tells us that we like the music – we knew that already.

In the second half of the talk he focuses more on the creation of music and the extent to which our biology can explain this activity. He discusses the sexual selection argument for music making and points out the flaws (as was done by Professor Fitch in this excellent review article)

He moves on to comment about the nature of examining creativity, a pursuit that he believes are in serious need of tasks that more accurately test the processes that they intend to represent. Thinking of all the different uses for a brick seems a little remote when considering the creation of a symphony, to his mind at least.

Finally, he discusses the nature of art and human consciousness and the unique human traits that have driven the development of artistic behaviour; mental freedom, unique knowledge, and drives that yearn to be fed and satisfied.

In conclusion, I know plenty of people who would argue long and hard with this man if they were in the room with him. Personally, I agree with some of his points and not others; at times I find him over romantic, somewhat over judgemental and so on. The point is however, that he is a well educated man with a love of music who has considered some of the best evidence that the neuroscience of music has proposed and found it wanting. For him, it simply does not answer the important questions for which he came looking for answers.

In conclusion, I know plenty of people who would argue long and hard with this man if they were in the room with him. Personally, I agree with some of his points and not others; at times I find him over romantic, somewhat over judgemental and so on. The point is however, that he is a well educated man with a love of music who has considered some of the best evidence that the neuroscience of music has proposed and found it wanting. For him, it simply does not answer the important questions for which he came looking for answers.

Although it is tempting to shout back we must try to welcome the insight, consider the points, and ultimately to think carefully about how best to respond to the critique (either by better communication of intent or improved experimental design) in order that we all can move forward in our understanding.

One Comment

Mark Riggle

The Tallis video was interesting, and of course, in the video’s first half, he is right about the real lack of insights to music pleasure currently provided both by neuroscience and by the current evolution scenarios for music’s origins. The second half was centered on a strange thesis that claimed that an understanding for that pleasure (in the neuroscience and evolutionary terms) was not really possible because music comes from a drive and a need to express something — probably something to do with emotions. That direction seems impossible to correctly reconcile with evolutions very simple requirements, and hence his claim that evolution was not required for it (although he thinks evolution is correct).

I would say that more likely our imagination has been too barren to find the correct evolutionary scenario that explains music. Interestingly, language origin explanations currently also lack adherence to ‘correct’ evolutionary requirements, but everyone (correctly) assumes one exists.

Fitch, Tallis, and others quickly dismiss sexual selection as a possible force for music selection because of the lack of sex-dimorphisms for music (differences for music ability between the sexes). The assumption they all make (including Miller) is that, for music sex-selection (by female choice), music must be an indirect fitness indicator. That is saying something like: you would need a healthy brain to do music, therefore doing music shows you have genes that thrive in the current environment (like peacock-tails) hence good genetic material for off-spring. The problem is that indirect fitness indicators must be sex-dimorphic (details omitted here but it is from the cost-benefit differences between the sexes for the trait), and therefore, because music ability is not sex-dimorphic, music cannot be an indirect fitness indicator and is thus not under sex-selection.

They are completely correct that music cannot be an indirect fitness indicator. However, other mechanisms also can drive sex-selection (by female choice) that are not indirect fitness indicators and hence do not drive a sex-dimorphism. The way these direct sex selection forces operate means they must eventually produce different cost-benefit ratios for males and females, and hence they will eventually become indirect indicators; however, music may not be at that particular turning point yet.

The sex-selection elephant in the room is the principle: for female choice environments, males who provide more pleasure to females gain a reproductive advantage. If you combine that with the certainty that music gives pleasure and the pleasure varies by performer, then how can sex-selection not be active? Of course it is; and music, because it is not sex-dimorphic, must be a direct indicator of something very useful.

I think I know what that useful thing is, but perhaps others would like to think about it too.