Musicophilia – real but poorly understood

What causes musicophilia?

If you go to any search engine and type in ‘musicophilia’ then you will more than likely be directed to the excellent book of that title by Oliver Sacks. In this book Sacks employs his familiar engaging and compassionate narrative of neurological patients to explore afflictions and treatments surrounding music. I have known many students to be first inspired to studying music psychology thanks to this enjoyable book.

If you go to any search engine and type in ‘musicophilia’ then you will more than likely be directed to the excellent book of that title by Oliver Sacks. In this book Sacks employs his familiar engaging and compassionate narrative of neurological patients to explore afflictions and treatments surrounding music. I have known many students to be first inspired to studying music psychology thanks to this enjoyable book.

Musicophilia is an excellent title for Sack’s book given its focus on both music-related phenomena and neurological patients. But many people do not realise that it is also a poorly understood neurological phenomenon. Patients who are diagnosed with ‘musicophilia’ report a sudden, abnormal craving for music and/or increased interest and responsiveness to musical sound.

Now, many of us crave music on a daily basis – myself included. But is that the same thing? Are we musicophilics?

Not as far as I can tell. I had a search of the internet for you (my pleasure, dear reader) and I couldn’t find any reference to the term ‘musicophilia’ being used to describe normal, everyday music listening habits, even when these habits reach extremes of time or financial consumption. Rather musicophilia describes when someone’s music listening habits and reactions suddenly go into overdrive, typically following a brain injury or illness.

Not as far as I can tell. I had a search of the internet for you (my pleasure, dear reader) and I couldn’t find any reference to the term ‘musicophilia’ being used to describe normal, everyday music listening habits, even when these habits reach extremes of time or financial consumption. Rather musicophilia describes when someone’s music listening habits and reactions suddenly go into overdrive, typically following a brain injury or illness.

The first of many tales within the book ”Musicophilia” contains one of the most compelling patient cases of this condition. A man was struck by lightning after making the unfortunate decision to attempt a phone call in a public booth during a storm. After the lightning strike the man was left with no long lasting significant cognitive changes (remarkable) with the excepting of a new raging passion for music, both in the form of listening and in learning the piano.

These cases, as you might guess, are rare. This fact might explain why there is relatively little literature on musicophilia and, consequently, why the phenomenon is poorly understood. A recent exception was a new paper by Phillip Fletcher and colleagues at the Dementia Research Centre at UCL (UK) who have looked into the brain basis of musicophilia in 12 patients.

All the patients in this study had frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), a term used to describe a range of dementia related diseases where the brain exhibits atrophy, or loss of grey matter.

The 12 patients in the current study who had musicophilia were compared against 25 patients who had FTLD without musicophilia. The groups did not differ in age, gender, or years of education and they performed similarly on tests of executive function, memory and visuoperceptual skills.

MRI scans were used to pinpoint any differences between the brains of FTLD patients with or without musicophilia. They also looked at the music listening interests of the two groups. Not surprisingly the musicophilic group spent more time listening to music. Interestingly the onset of the condition was often marked by a change in genre preference, e.g. from pop to jazz.

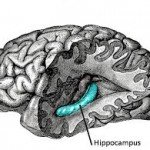

In terms of the brain scans, the musicophilic group showed significantly increased regional grey matter in the left posterior hippocampus (a memory area) compared to the non-musicophilic group. There were other less impressive differences in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortices and anterior cingulate. Interestingly the musicophilic group showed lower comparative grey matter volume in the posterior parietal cortex, medial orbitofrontal cortex, and frontal pole.

In terms of the brain scans, the musicophilic group showed significantly increased regional grey matter in the left posterior hippocampus (a memory area) compared to the non-musicophilic group. There were other less impressive differences in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortices and anterior cingulate. Interestingly the musicophilic group showed lower comparative grey matter volume in the posterior parietal cortex, medial orbitofrontal cortex, and frontal pole.

This new paper gives an initial idea of the kind of neural signature that might underlie the symptoms of musicophilia. The authors noted that the network that they found corresponded well with the so-called ‘default network’ which helps to mediate internally directed thought. Also, they saw activity in areas associated with assigning ‘salience’ to social signals and understanding the mental states of others. Finally, and most expected, they found areas associated with musical memory and emotional response.

What does all this mean? The authors conclude that a sudden abnormal craving for music in this patient population represents a shift in interest away from social signals and towards the “…more abstract hedonic valuation that music represents”.

In other words, music may become an internal system of meaning for the person with its own unique cognitive reward, which the person generally then seeks less from the world around them.

Why music suddenly gains such a high degree of emotional value for musicophilics is not a question that is resolved by this research. It also remains to be seen how musicophilia relates to other obsessive or ritualistic behaviours that can develop in FTLD patients. However, this research does confirm that there is a neural ‘reality’ to sudden onset music obsession, and that the memory and emotion roots of music are one reason why it becomes so salient for musicophilics.

Why music suddenly gains such a high degree of emotional value for musicophilics is not a question that is resolved by this research. It also remains to be seen how musicophilia relates to other obsessive or ritualistic behaviours that can develop in FTLD patients. However, this research does confirm that there is a neural ‘reality’ to sudden onset music obsession, and that the memory and emotion roots of music are one reason why it becomes so salient for musicophilics.

4 Comments

Tiffany

I have played the clarinet for about 5 years now; I’m a musical person. A little over a year ago I tried to commit suicide and suffered severe memory problems since then. Also since then, I’ve felt as if, if I don’t have music, I can’t function. While listening to some songs, none of which are classical.mind you, I get these odd, hard to describe feelings. I was wondering if this is a possible type if musicophilia.

vicky

Hello Tiffany. Thank you for your comment. You may indeed have a form of musicophilia though the condition is rare. I am afraid I am not able to offer diagnosis over the internet so I always suggest to attend your doctor for advice if you are worried about your reactions to any stimulus, including music. But if your positive feelings that are inspired by music are helpful to you then it is quite possible that you have found a wonderful form of support for life; a flexible, safe and personalised sound that is unique to you. I wish you all the very best for the future.

Michael Barker

Hey! How would I go about diagnosing my musicophilia. I have strange out of body experiences that other people don’t. I have a bizarre craving and love for music, I see and feel music is a lot more ways that people do. I’ve also had head trauma experiences as a child so that might play something into it. Anyways how would I go about diagnosing it?

vicky

Hi Michael. Good question. At the moment there are no tests from musicophilia. It is a really interesting question. People have looked a lot at people who don’t react to music (anhedonia) or who have a difficulty in processing music (amusia) but really not much at the other end of the spectrum. I would love to know more about this area myself – as with all researchers I get fascinated by topics but I have to be careful not to try to run too many projects at once. I would suggest, as a starting point, that you might contact the authors of the paper I wrote about in this blog. They might be keen to hear more from you or, since they work in the area, could pass you on to people in the field. Start with Jason Warren at UCL – https://iris.ucl.ac.uk/iris/browse/profile?upi=JDWAR75