How can we capture earworms?

Hello Dear Reader,

I am currently on maternity leave, awaiting the arrival of my first baby, my daughter. It has been a busy last few weeks at work as I did my best to complete as many of my work projects as possible and ensure that everyone I would be leaving behind at Sheffield for a while would be okay. In particular I found it hard to face the idea of leaving my Music & Wellbeing team for this period of time. However, they are all doing really well on their individual projects and I know they have good support and great strengths going forwards. They have all been incredibly supportive of me during my pregnancy and above everything else I am grateful for their understanding and kindnesses. I am lucky to work with such lovely people.

I have been lucky with my pregnancy when I look back. Yes, I was tired a great deal of the time, but for the most part I was blessed with only mild symptoms for the best part of 8 months. That has not been the case for the past few weeks – I have been more sick, exhausted and uncomfortable than ever before in my life. My consolation is that my baby girl is strong and doing well. In fact, she is kicking me as I type! If all goes well her Papi and I will get to hold her very soon for the first time – we can’t wait.

Today’s blog is dedicated to a project that has taken a few years to come to the light. Back in 2010-2011 I began working on the earworm project, a collaborative series of studies that had been devised between myself and my senior colleagues at Goldsmiths, University of London.

We wanted to understand why music gets stuck in our minds – the secrets behind the pervasive and everyday mental experience of an earworm.

During my time at Goldsmiths we carried out several studies where we investigated:

2 – What gets rid of unwanted earworms?

3 – What are earworms like for other people?

One of my final big questions of the project emerged from a growing concern we had with studies that focused on earworm induction. These studies attempt to trigger a realistic earworm experience in the lab so that experimenters can then carry out tests on various aspects of the earworms, such as how long they last or who gets them more frequently. Another aim of induction studies is to determine where earworms may originate in the brain.

The problem with many of these earworm induction studies is a basic weakness in their method – they risk biased responses by the use of leading questions. For example, you might be invited into the lab and asked to listen to some music. Then after a period of time, perhaps engaged in another activity, you are asked the question; ‘Have you had that music we played you stuck in your head?’

The problem with many of these earworm induction studies is a basic weakness in their method – they risk biased responses by the use of leading questions. For example, you might be invited into the lab and asked to listen to some music. Then after a period of time, perhaps engaged in another activity, you are asked the question; ‘Have you had that music we played you stuck in your head?’

This question betrays the nature of the earworm induction and leads the participant to a certain response. Of course, most if not all people will tell the truth, but you can’t be sure if they would really have really responded in this way if you had not prompted them. The same logic applies to leading questions in eyewitness testimony.

Hence, we decided to try to develop a new method to induce earworms with one main goal – participants must not know that earworms are the aim of our experiment. They must be unaware that we are inducing earworms and unaware that they are reporting on earworm experiences.

As you might imagine, this was a hard puzzle to crack! And it took time…

To begin with I spent many hours hunched over my desk, pouring over eyewitness testimony research and memory literature to find inspiration for the new paradigm. I also wanted the new earworm induction method to bear some relationship to how earworms happen in everyday life. So I also went back to our previous surveys and read the thousands of stories we had received describing the circumstances of earworm onset.

Eventually, after quite a few false starts (many pilot experiments ended up in the bin…) I had an idea. Many people get earworms after watching films, adverts and television so it would meet our criterion to reflect real life experiences if we used these kind of media for our trigger.

Eventually, after quite a few false starts (many pilot experiments ended up in the bin…) I had an idea. Many people get earworms after watching films, adverts and television so it would meet our criterion to reflect real life experiences if we used these kind of media for our trigger.

However, there was a problem. Basic TV scenes and TV/ radio adverts didn’t seem to work very well, nowhere near as well as I had expected. I carried out one pilot using radio jingles and I could not believe how few really stuck in people’s minds.

I decided on a new tactic. I wanted to try to find adverts or film clips that were mostly music as I had a suspicion that the problem of low induction in my pilot studies was related to the amount of new information carried in the verbal messages of the adverts. People may have been too distracted by the complex nature of the new stimuli, meaning the ‘earworm potential’ was weakened. I wanted to find short visual clips that featured only music, preferably music that would be familiar to most people as this tends to maximise the chances of successful earworm induction as compared to novel music.

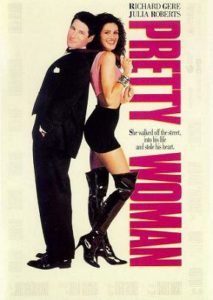

After a few hours of searching YouTube I finally came upon the visual clip that broke the puzzle – one of the original film trailers for the 1990 film ‘Pretty Woman’. This film trailer, which was really released in cinemas, featured only visual clips of the film to the soundtrack of Roy Orbison singing the title track ‘Pretty Woman’. No spoken words. Perfect.

Once I knew what to search for the other examples of film clips for the new paradigm came pretty quickly. James Bond was an obvious choice of a well known musical theme where I was pretty sure I could find a trailer that only used the famous leitmotif to visual images of Bond doing his thing. And I found one, a trailer Daniel Craig’s version of ‘Casino Royale’.

Musical films were another productive avenue. I found a very nice trailer of the 2012 film ‘Les Miserable’ that featured only visual clips of the film set to the haunting rendition of ‘I Dreamed a Dream’.

In the end we decided on a paradigm that featured two suitable music-only film trailers, as we wanted an induction that was not too long, which could be done in a classroom or citizen science project setting in 10-15 minutes. We went for the ones that worked best – Pretty Woman and James Bond.

Around the lab the new paradigm became known by the name of its original inspiration. It was, and still is for me, ‘The Pretty Woman Paradigm’

The other key invention in the paradigm is the way that we sampled the experiences people have after they have seen the induction film trailer stimuli. We don’t ask the direct leading question that is so troublesome in other studies. Instead we created our ‘Mind Activity Questionnaire’. Inspired by eyewitness testimony research, the idea is that the questions we ask are wide and varied, they don’t focus on music but on all mental experiences that people have during the intervening period between induction and final reporting. Also, we get people to rate their level of perceived mental control over their experiences and the amount of repetition in their thoughts. Using these criteria, experimenters can distinguish the mental experience of earworms (involuntary and repetitive) from other mental imagery of music, which may well be entirely voluntary and therefore not, by definition, an earworm.

Using ‘The Pretty Woman Paradigm’, my coauthors and I have just produced a new paper showing the influence of cognitive load on earworm induction. We found that it actually takes surprisingly little distraction to get in the way of an earworm setting up in our minds (link to paper below).

This new evidence supports the idea that one important factor that predicts an earworm experience that originates from music exposure is the existence of a wandering mind state in the period of time shortly after the music is heard. It appears that a diffuse state of mental attention at this point in time provides fertile mental soil in which an earworm can embed itself within our conscious focus.

More recently, my close colleague on this paper and in life, Dr. Floridou (the lovely Georgina), and I have been working on a new project at Sheffield with Dr Lisa-Marie Emerson, using ‘The Pretty Woman Paradigm’. We have been testing the differences between earworms and other forms of intrusive mental experiences.

More recently, my close colleague on this paper and in life, Dr. Floridou (the lovely Georgina), and I have been working on a new project at Sheffield with Dr Lisa-Marie Emerson, using ‘The Pretty Woman Paradigm’. We have been testing the differences between earworms and other forms of intrusive mental experiences.

That research project has gone really well and is in the final process of being written up for publication; stay tuned! Hopefully later this year we can bring you lots of new and fascinating insights into the hidden world of our sometimes seemingly random subconscious thought processes.

That’s it for now, Dear Reader. I must turn my attention away from work for a while and towards my family and my new life as a mum. I intend to devote my energy over the next few days/ weeks into preparing to bring my daughter safely into the world. A whole new world awaits me and my loved ones. Please wish us luck 🙂

Links

Here is a link to our new earworm paper, featuring ‘The Pretty Woman Paradigm’, which was published by The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. It is called ‘A novel indirect method for capturing involuntary musical imagery under varying cognitive load’