Can tone deafness occur in typical listeners?

Hello Dear Reader,

I am just returned from ICMPC 2018 in Graz, Austria. It was a difficult trip on a personal level as it was my first time I have been away from my little girl for more than a day. I decided to compromise on a 3-day trip (half the event) to combine the joys that come with meeting colleagues at a conference while minimising the discomfort that is natural for me when I am away from my little Penelope.

I am just returned from ICMPC 2018 in Graz, Austria. It was a difficult trip on a personal level as it was my first time I have been away from my little girl for more than a day. I decided to compromise on a 3-day trip (half the event) to combine the joys that come with meeting colleagues at a conference while minimising the discomfort that is natural for me when I am away from my little Penelope.

It was wonderful to spend time with my colleagues and friends. We get together so rarely and the social times we spent together in this pretty southern Austrian town were fantastically fulfilling. I enjoyed all the talks and posters I was able to attend. I even managed to squeeze in some research project planning; there may be exciting new experiments in the pipeline soon!

It was wonderful to spend time with my colleagues and friends. We get together so rarely and the social times we spent together in this pretty southern Austrian town were fantastically fulfilling. I enjoyed all the talks and posters I was able to attend. I even managed to squeeze in some research project planning; there may be exciting new experiments in the pipeline soon!

Then, after the long trip home, my tiny girl ran a dozen wobbly steps into my arms, beaming from ear to ear while letting out a high pitched squeal of delight. It doesn’t get better than that!

Looking back, one of my highlights was seeing the posters from my PhD and postdoc researchers. I am lucky to work alongside these fine early career academics and I was super proud to see their hard work displayed for our community to enjoy. Here you can watch the talk given by my postdoc Dr. Georgina Floridou, on how earworms change as we age (from 10mins in).

The subject of today’s blog is a paper I came across while searching literature during my stop over in Amsterdam. It is called Random Feedback Makes Listeners Tone-Deaf by Dominique Vuvan, Benjamin Zendel & Isabelle Peretz. Some of you may know that one of my early research projects focused on the experience and aetiology of congenital amusia, a neurodevelopmental condition more commonly known as ‘tone deafness’. Is it really possible that disordered auditory feedback may replicate this experience in typically listeners? I was intrigued…

Individuals with CA have a lifelong difficulty detecting tonal variations, despite evidence that they may have subconscious ability to process the same musical sounds in line with typically developing individuals. The current theory is that there is neural disruption that prevents the correct conscious analysis of tonal information received from a normally functioning auditory cortex.

Our studies showed that ideas regarding disconnection along white matter pathways need to be taken with caution. However, there is good evidence that at some point and in some way, normal messages about tonal sounds from the auditory cortex become disrupted during attempts at processing by the higher brain centres. A key candidate is the the inferior frontal gyrus, which is critical for conscious access to pitch representations.

The study attempts to replicate tone deafness in a behavioural set up. During a ‘spot the odd note’ task, participants in the experimental group were given random feedback on their performance – they were told there were correct on 50% of trials regardless of their accuracy.

The study attempts to replicate tone deafness in a behavioural set up. During a ‘spot the odd note’ task, participants in the experimental group were given random feedback on their performance – they were told there were correct on 50% of trials regardless of their accuracy.

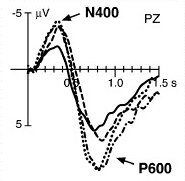

The hypothesis from this manipulation was that over time this feedback would reduce accuracy and confidence in their responses as well as mute a late positive brain response (measured in EEG, called P600), a pattern of neural anomaly found in amusics during their normal task performance.

Method

The 18 people in the experimental group heard a set of 40 short melodies previously used in amusia studies. There were four different versions of the set resulting in a test battery of 160 melodies. Each person completed a baseline set (where the feedback was honest), followed by two sets with the random feedback, and then finally a ‘recovery’ set where correct feedback was again given. Presumably this last test exists mainly to restore their confidence in the world at that point!

Results

Not surprisingly the control group (N = 20) did better overall than the experimental group. The experimental group also showed the predicted trend in that their accuracy fell over the random blocks and increased towards baseline again during recovery. Confidence followed a similar pattern.Finally the authors reported a decrease in the the amplitude of the P600 brain response to tonality violations, with no changes to earlier EEG components.

Discussion

The results are pretty clear; in the face of random feedback, people perform worse on a ‘spot the difference’ tone task. They begin to look more like a population with amusia in that their accuracy and confidence gets worse and in parallel a brain response related to tone processing is altered.

Do I believe that this paradigm replicates tone deafness?

Do I believe that this paradigm replicates tone deafness?

I have doubts. It is a neat experimental idea but I am concerned that the paradigm may only induce a lack of confidence response.

Put yourself in the place of a participant in the experimental group. The world no longer makes sense suddenly so you second guess yourself; perhaps you start pressing random buttons as you are convinced that the task is either broken, too hard, or that you failed to read/ understand the instructions.

The authors asked for post task feedback, a nice touch in the paper. However, in line with my concerns, only 7 out of 18 people reported that they noticed something strange in the feedback. This strikes me as bizarre. Did 11 people without amusia just suddenly accept they were unable to spot an out of key note? This speaks to me more about confidence than anything perceptual.

My own experience with amusia tells me that people living with this condition struggle immensely with confidence when it comes to musical tasks. Very often in the lab they would adopt a strategy of saying ‘same’ to each trial, convinced there was no point in listening to the sounds as they knew from a lifetime of experience that they couldn’t do it.

You have to try hard to make sure you mitigate against this strategy as it will destroy your data. You must be encouraging and make sure that your participants with amusia feel the confidence to give the tonal tasks a good try. I also remember the look of peace that would descend when we started a control task, be it visual or speech based.

So yes, the false feedback paradigm used here mimics amusia to the extent that it gives people a sense of unease when facing a tonal challenge, but that doesn’t mean that similar underlying psychological/ neurological activity drives both responses. The idea that this is paradigm is the behavioural equivalent of a TMS study, which causes genuine brain disruption, is a step too far at this stage.

The change in the ERP P600 response is intriguing. However, I don’t believe it is fair to claim that this indicates a sudden disorder in tone processing. In reality we don’t know what it was about the false feedback situation that caused the change in the ERP. I would like controlled systematic studies looking into influences on this ERP response, guided firstly by deeper insights into participant responses – what did they think was happening at the time and how did they chose to react.

The change in the ERP P600 response is intriguing. However, I don’t believe it is fair to claim that this indicates a sudden disorder in tone processing. In reality we don’t know what it was about the false feedback situation that caused the change in the ERP. I would like controlled systematic studies looking into influences on this ERP response, guided firstly by deeper insights into participant responses – what did they think was happening at the time and how did they chose to react.

What I would like to see more than anything is a control task. Do the same manipulation (ideally within subjects) with feedback on a task involving facial judgements or number calculations – do you get a similar performance change? If so, then there is good evidence you have produced a general confidence impact effect. That is the simpler explanation than claiming you are inducing amusia, prosopagnosia, or dyscalculia. See Occam’s razor 🙂